By Phil Treseder

Swansea Museum Education & Participation Officer

In January 2024 a film was realised with the title ‘One Life’. The film is based on the true-life story of Sir Nicholas Winton who is played by Sir Anthony Hopkins.

The film focuses on a scrapbook which was put together by the Committee for Czechoslovakian Child Refugees in 1939 and given to Nicholas Winton. The group supported Nicholas Winton in organising Kindertransport trains of child refugees out of Czechoslovakia in 1939 to escape the Nazis.

The scrapbook is now in the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem.

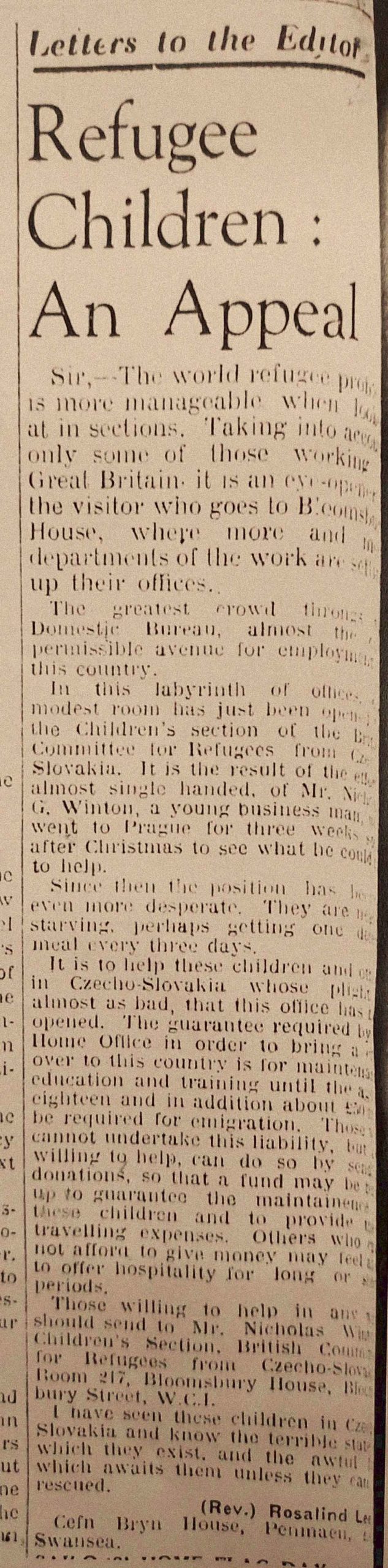

In the film, Nicholas Winton browses the scrapbook and stops at an article titled `What they have done to the Czechs’. In the real scrapbook, to the left of that article is a newspaper cutting from the South Wales Evening Post. It is a letter to the Editor dated 20th of April 1939, headed `Refugee Children; an appeal’. The letter is from the Rev. Rosalind Lee, Cefn Bryn House, Penmaen, near Swansea.

The Rev Rosalind Lee was born in Edgbaston, Birmingham but would later settle in Swansea at Cefn Bryn House, Penmaen, with her brother who was a lecturer at Swansea University. The house still exists and has a spectacular view of Three Cliffs Bay. Both were actively involved in the Gower Society. The Rev. Lee bought several plots of land on the Gower to stop any development on them and then donated the land to the National Trust.

She became a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse during the Great War and then became a Minister with the Unitarian Church in 1919. She was a member of the first committee of the British League of Unitarian Women from 1908 and become the National Secretary in 1929. She would later be elected as President of the Unitarian General Assembly in 1940.

The Rev. Lee served as a Minister in Treorchy, Leicester, Hackney, and Stourbridge and as a district minister in South Wales.

In October 1939 she went to Prague to set up and run a `Friends Refugee Office’ with another Unitarian Minister John McLachlan. They worked closely with Doreen Warriner, the only one of the three they include in the film.

A full list of the 669 mainly Jewish children they saved are online. Unfortunately, the last train due to depart on the 1st of September 1939 with another 250 children on board, was prevented from leaving by the outbreak of the war and the majority of those children were subsequently murdered.

The British Government would not allow the transport of the children without guarantors in place who would look after the children and cover the costs.

The list of children includes information on names, dates of birth, and address’s in the UK and who the guarantor was. From the list we can see that the Rev. Lee was guarantor or co-guarantor for many children.

Not all were based in Swansea, some she obviously managed to place with family and friends. Some of the many children included were:

Ivo Englander, born 1924.

Eduard Kestenbaum, born 1930.

Ervin Kestenbaum, born 1926.

Renee Kestenbaum born 1928.

Katarina Kestenbaum, born 1931.

None of the above children would return to Czechoslovakia. The two Kestenbaum sisters Renee and Katarina would both, following the war, emigrate to the United States. The brothers Eduard and Ervin would later apply for British citizenship in 1947 and remain in the UK. At the same time, they both changed their surname to Berry.

It appears that Eduard may have moved to Birmingham, whilst Ervin remained in Swansea.

A search of the Czechoslovakian Holocaust victims list under Kestenbaum only produces two names who may have been their parents. Frantisek, born in 1898 was murdered on 13th August 1942 at Majdenek. Hana (although on the record spelling is slightly different, probably a spelling mistake by the SS) was born 1897, and was murdered, place and date unknown.

The surname, Englander appears to be fairly common, so we were unable to locate the parents of Ivo, but it is probably safe to assume they were also murdered.

If they did survive the war, they would have been devastated to find out their son did not. Being the oldest of the five, Ivo became eligible to join up and he joined the Czechoslovakian Air Force operating in Britain.

He was killed on the 1st of January 1945 whilst returning from patrol with Coastal Command. In severe weather his Liberator plane crashed into the northern end of the Island of Hoy, Orkneys.

His body was taken to the mainland, and he is buried in Tain Cemetery, Scottish Highlands.